I believe we are on the cusp of a second golden age of geography. During the first wave, we were on offense. Cartographers during the Renaissance held the keys to unlocking unprecedented understanding about the scope and nature of the world.

But the “second coming of geospatial” that we’re about to live through is all about defense. Climate change is a clear and present threat to humanity’s cumulative wellbeing. The race is underway.

Time is Against Us

There is a dire need to take immediate action to reduce atmospheric carbon (even assuming we manage to reduce greenhouse gas emissions globally through cleaner energy sources).¹

The good news is that the global transition to renewable energy is in full swing. Wind and solar are on pace to be a cheaper source of energy than coal in all major markets by 2030.² When I look at this chart, I’m struck by how incredible it is to be living through such a dramatic inflection point in real time.

The bad news is that we’re collectively realizing that simply reducing emissions is very unlikely to stave off a disastrous mass extinction along with a host of other horrifying consequences. At the infamous 2º Celsius warming threshold, about 18% of insects, 16% of plants, and 8% of vertebrates will see their natural habitat shrink by half or more.³ Drought, flooding, wildfires, sea level rise, vector-borne diseases, and other biblical plagues await us at unnerving levels.

We must therefore move beyond emissions reduction to also reduce the existing pool of atmospheric carbon, which is going to require radically improved land use management at global scale.

Understanding and managing land is where I believe geospatial technology will play its most highly leveraged role over the coming decades. We’ve been cataloging the Earth’s contents in increasingly fine-grained detail for millennia — now we’re going to be forced to make dramatic choices about its composition over the next decade or face entirely avoidable and horrifying consequences.

The thing is…we don’t need a technology breakthrough. We need a resource allocation breakthrough.

Competition vs. Collaboration at Species Scale

I sometimes find myself fighting for scraps with our competitors at Azavea. For better or worse, I tend to adore them. I don’t know what it is about geospatial software that attracts such incredibly charming people. Maybe it’s because there’s not much money in it.

The trouble is that while we’re all busy spending discretionary R&D dollars on open source projects and standards to try to make collaboration easier, we almost never actually get paid by clients to collaborate. When you only get to spend 10% of your time on massive problems that require industry-wide coordination…you don’t tend to solve them.

When I say “we have the technology,” I’m being a little facetious. But only a little. What would you need in order to make detailed plans for saving the world from cataclysmic climate change in the next few centuries? I’d start with a map of every corner of earth, updated in real time, with logic built on top of it to model the effects of any decision in the near- and long-term.

I know a handful of firms that could build that tool today. I just don’t know who would pay them to do it.

What a Solution Looks Like

In order to manage land use with the efficacy required to slow and eventually stop climate change, the first thing you need is high resolution data of the earth’s land cover. “Resolution,” in this instance, refers to four complementary characteristics:

Spatial (what shapes are visible?)

Spectral (what physical properties are parsable?)

Temporal (what frequency does the data update at?)

Dimensional (what depth do features on the surface have?)

How could we possibly get information like that for every point on earth on a regular basis? We kinda already do.

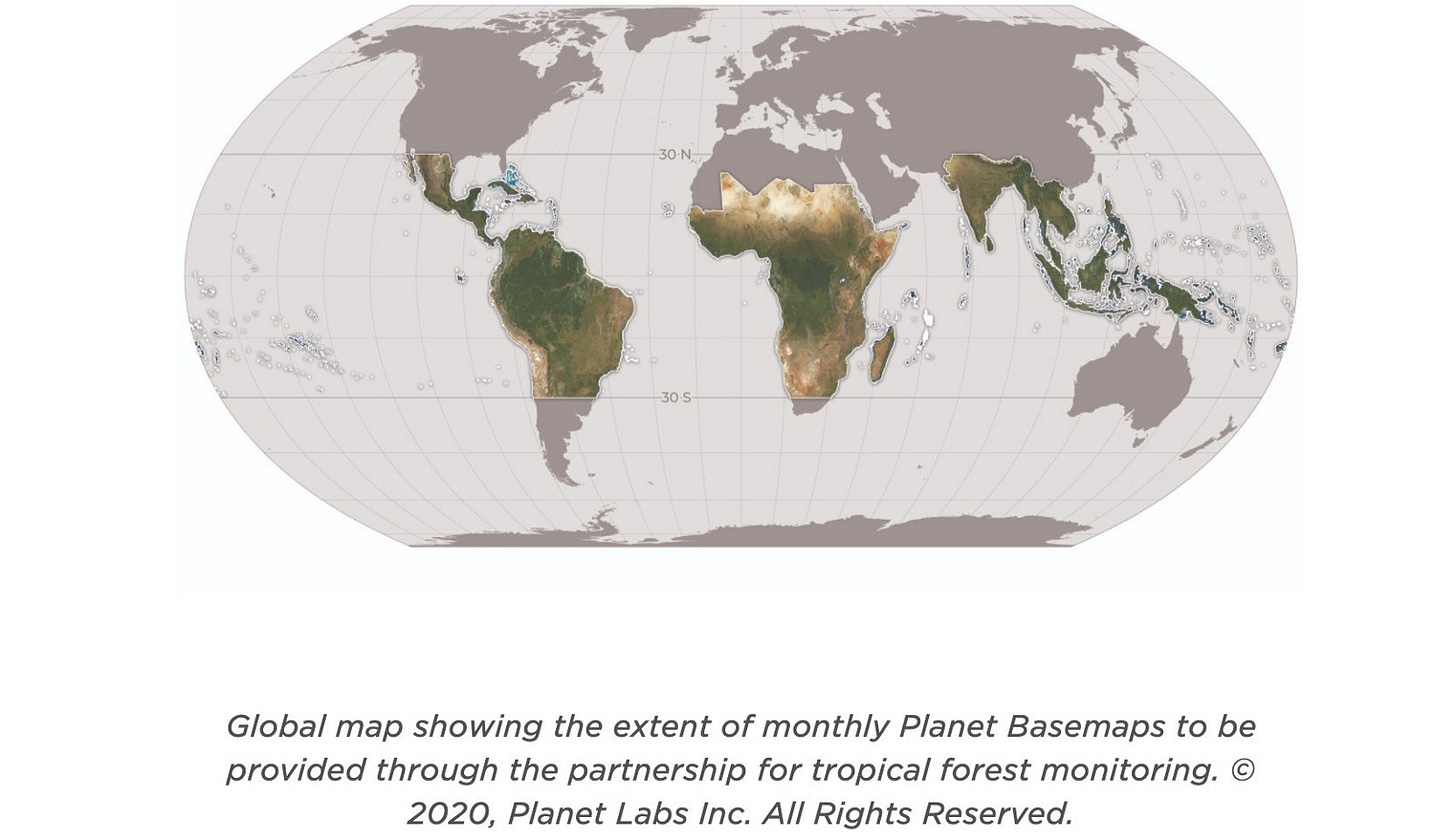

Last month, in Partnership with Norway’s International Climate and Forests Initiative (NICFI), Planet Labs announced that they’ll be releasing a monthly basemap for most of the central swath of the world. You can scroll around at look at it here. It’s pretty incredible.

That’s a start. More exciting developments are underway. For starters, there’s the Synthetic Aperture Radar revolution currently underway that I’ve written about previously — SAR will inch us further toward affordable, global-scale monitoring of land cover change in perpetuity.

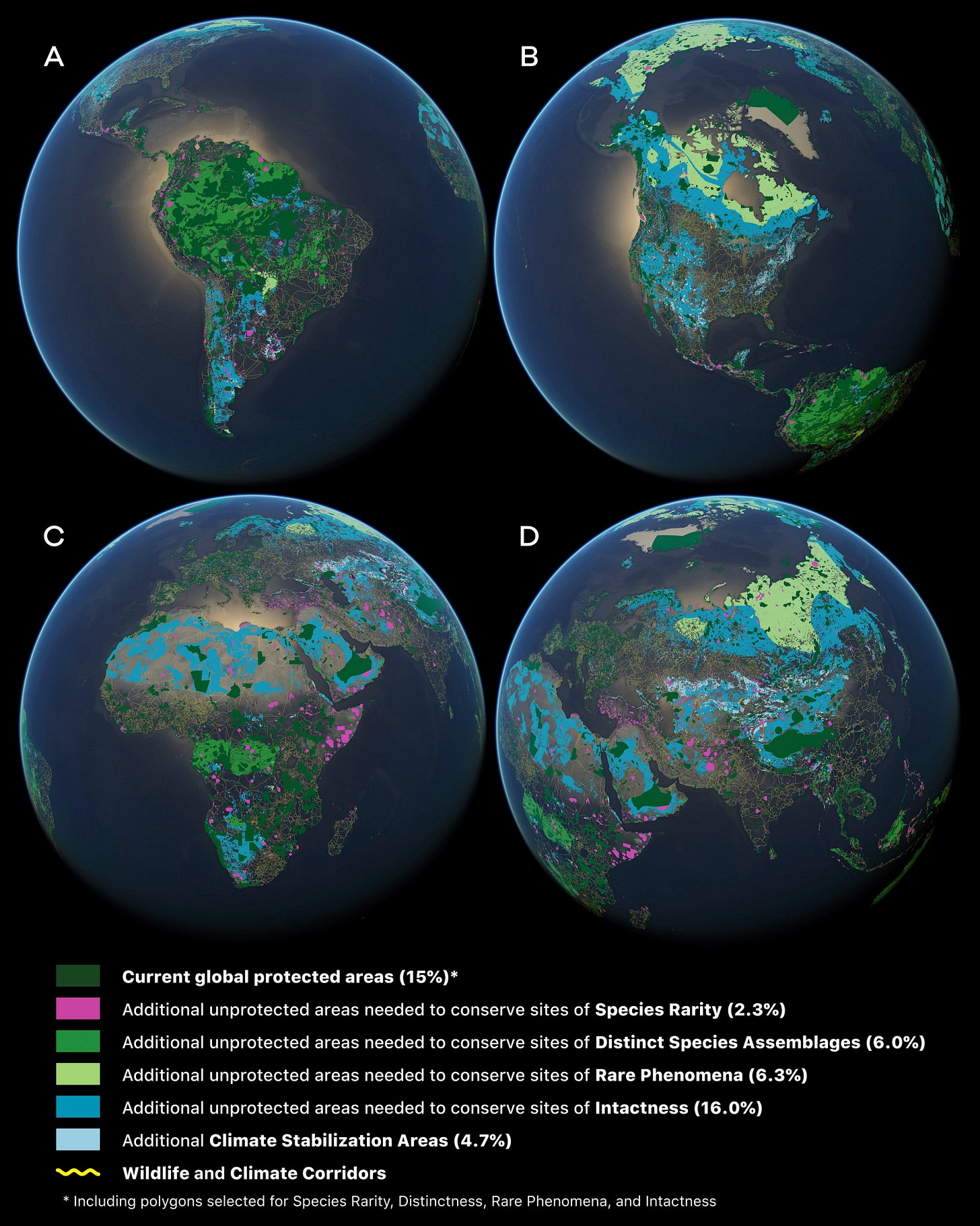

And just at the horizon, work like that of Greg Asner’s Center for Global Discovery and Conservation Science at Arizona State University hints at the kind of detail we can expect to derive from hyperspectral sensors capable of breaking down the electromagnetic spectrum into minute, individuated channels of light that allow for incredibly detailed characterization of ecosystems and landscapes. His recently published work, the Global Safety Net, revealed a shocking return on informed land use management:

We estimate that an increase of just 2.3% more land in the right places could save our planet’s rarest plant and animal species within five years.

New organizations are popping up constantly to carve out a niche within this massive puzzle — recently, National Geographic spun out a new firm called Impact Observatory that aims to provide policy makers with some of the land planning tools I have been hinting at throughout the piece.

Meanwhile, quiet but important initiatives like the Spatio Temporal Asset Catalog (STAC) standard, Cloud Optimized GeoTiffs (COGs), and the Open Geospatial Consortium API Features effort are crafting the common languages that most of these various efforts will eventually speak.

Prototypes are being built. Standards are being written. But mostly, we’re all working in isolation on our own branded repackaging of the same basic idea.

A Call to (Collective) Action

I want to work with our competitors on huge projects trying to make a small dent in the fight against climate change. I think many of them feel the same. Unfortunately, we simply can’t afford to collaborate the way we’d like to right now. As it turns out, it’s extremely hard to get individual entities to pay for a collective good.

What can be done today to expedite progress on understanding and mitigating climate change using geospatial technology? I implore major funders of climate-related work to consider the following four suggestions:

Design projects that encourage collaboration between potential bidders. I’m not suggesting that you should eliminate competition for the work. On the contrary — make vendors continue to earn their spot by regularly bidding new work to a shortlist of vetted firms on “Indefinite Delivery/Indefinite Quantity” (IDIQ) contracts. Refresh the list every few years. For truly massive, long-term projects the last thing you want is to grant a monopoly to a firm that will naturally drift toward building idiosyncratic and bloated software.

Invest in open standards and open source tools. The Radiant Earth Foundation has consistently hired one fellow at a time to work on critical open standards like STAC and COGs. The OpenStreetMap Foundation is just now finally able to hire its first engineers to dedicate themselves full-time to OSM tooling. These are foundational technologies used by the largest multinational corporations in the world, but they’re being funded in drips and drabs by scrappy charitable groups and informal networks of volunteer software engineers. If you use open tools that are directly applicable to climate-related work, and you are weighing the choice between buying back billions in your own stock or making a few strategic acquisitions, maybe consider setting a little aside to start pulling your weight.

Subsidize private data that has become a public good. The data that will underpin climate-focused geospatial applications will not be cheap to produce. While incredible initiatives from governmental groups like the European Space Agency and NASA have resulted in troves of valuable, global-scale data, commercial entities collecting similarly valuable data can’t afford to just give it all away for free. Choosing to partner with private sector data providers to create essential public goods is, in my view, the job of governments and intergovernmental groups. NICFI’s investment in the recent data dump from Planet is a great early example. I hope to see more of that in the coming years, especially with some of the new SAR providers.

Make government work more accessible to non-traditional contractors, including unclassified DoD projects. I work for a company that does not work on technology that supports war fighting. But that doesn’t mean we won’t work with the military — in the United States, funding for disaster response, resilience and preparedness, critical infrastructure management, and even foreign aid is often concentrated in the DoD (for better or worse). You need a PhD in bureaucracy to know how to find, let alone navigate, the average military contracting process. A great example of a sane entry point for non-traditional contractors is the Defense Innovation Unit which uses a combination of tightly scoped RFPs and rapid procurement processes to make DoD projects more attractive to tech companies. More of that for non-warfighting projects, please!

¹ For a nice summary, I recommend Nat Geo’s accessible primer from last year, To curb climate change, we have to suck carbon from the sky. But how? For a deeper explanation of the various paths to halting global warming at 2ºC, the The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s Special Report is worth a look.

² Wind and solar plants will soon be cheaper than coal in all big markets around world, analysis finds, The Guardian, March 2020.

³ A Degree of Concern: Why Global Temperatures Matter, NASA Global Climate Change Website, June 2019