Open All of the Satellite Imagery Archives

A moral and economic argument for ushering in the global monitoring revolution that the world urgently needs

The argument below is just my personal opinion, and you should view it skeptically considering I am a financially conflicted and active participant in it. And like always, please don’t conflate my opinion with those of my ✨employer✨.

Earlier this month I put forth a meandering argument as to why satellite imagery providers should open their archives to the world for free, and I was totally floored by the response I got to it.

Lots of people reached out to say that they agree—and not just customers, people working at the satellite imagery companies I was poking at, too! I’d like to expound those ideas.¹

What Happens When You Give Away Your Archive

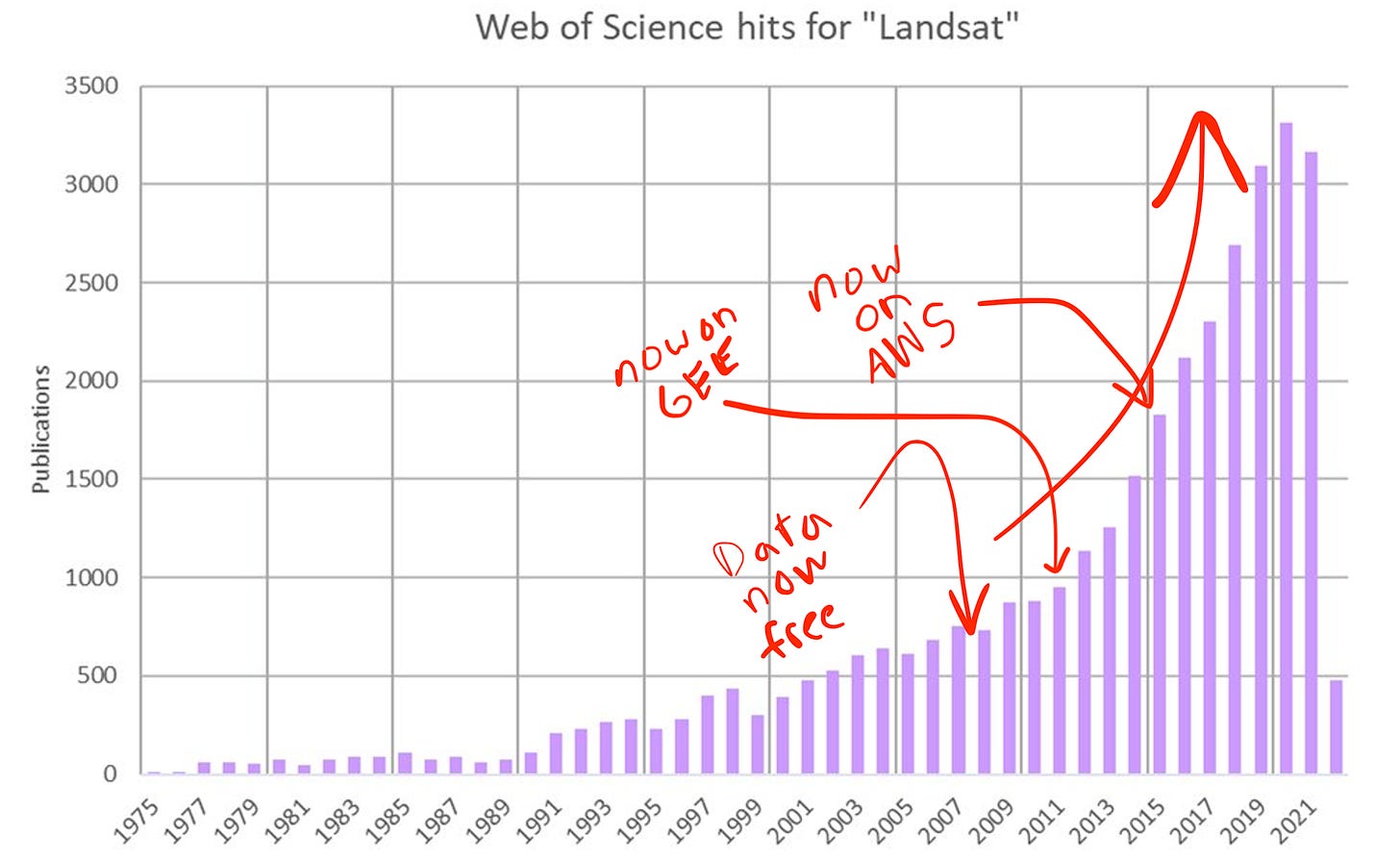

Have you ever looked at a chart of the academic publications containing papers that reference Landsat over time?²

That’s a hockey stick, baby. Ex-po-nen-tial.

Raw number of publications per year probably isn’t a perfect proxy for utilization, so let’s look at downloads:

Why does that chart begin in 2009? Because, in 2008 USGS first instituted the policy of giving away Landsat data for free (first with Landsat 7, then the rest of the archive in 2009).³ It probably felt like a crazy choice at the time after billions of dollars of investment in the program… but the effect was immediate and extraordinary. Roughly a 100-fold increase in downloads in a decade.⁴

But even that’s not the whole story!!

In 2010, Google’s Earth Engine project was unveiled with the entire Landsat archive already loaded in. By 2015, AWS had ceremoniously added the Landsat archive to its free “Earth on AWS” repository. Two years ago Microsoft joined the party with the launch of their “Planetary Computer” initiative, which also hosts Landsat data. Hardly anyone I know downloads Landsat scenes anymore - for planetary scale analysis, you tend to “bring the algorithms to the imagery.”

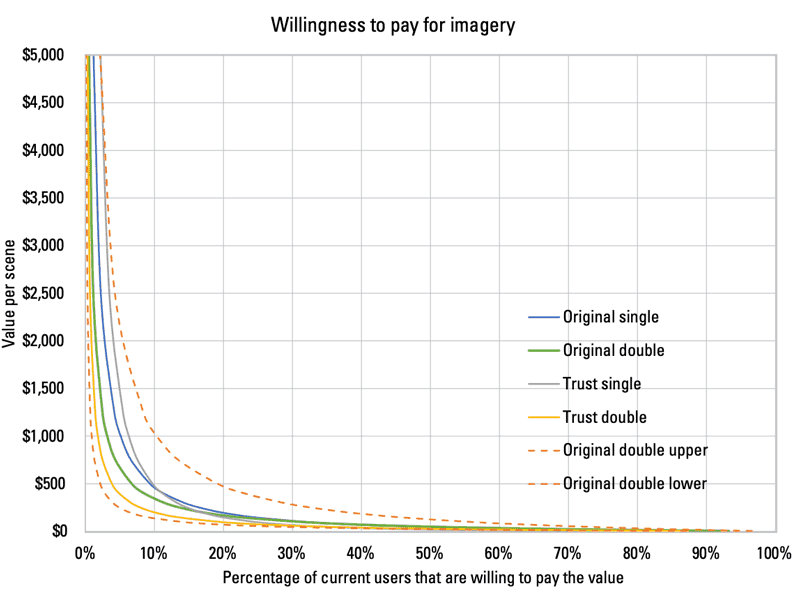

It’s hard to quantify the value of Landsat, but the last time USGS tried in 2017 they estimated that it produces $3.45B in value to society annually. There’s a second important conclusion buried in that study: if they tried charging for the data, that value would likely vanish in the blink of an eye:

Here’s the horrible paradox of satellite imagery archives: they are simultaneously the most tangible, compounding asset satellite imagery constellations create over time… and yet the vast majority of users are categorically uninterested in paying for access to them.

A Moral Argument for Giving It All Away

If Landsat creates billions in annual value to society annually…imagine what the value to society would be if Maxar, Airbus, and Planet released their archives! Those repositories contain data with up to 100x the spatial resolution and 10x the temporal revisit of Landsat…

And just like Landsat data is more valuable due to the availability of Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 data to combine it with, releasing commercial archives would have a multiplicative effect.

But to a lot of people in the industry, the idea of just giving away the archive is… unthinkable? Ludicrous. Self-sabotaging, impractical, unsustainable. In a word: stupid.

However, few would disagree that opening up commercial archives would lead to an explosion of new research and entrepreneurship that would greatly benefit society writ large, just as the opening of Landsat’s archive precipitated a little more than a decade ago. To be fair, there are some people who disagree that opening up access would have any net effect—I’ve drawn a helpful diagram to describe that type of person:

While I do not have access to their books, I feel comfortable speculating that Maxar, Airbus, Planet and the rest do not rely in any meaningful way on revenue from data collected 5+ years ago.

And yet, those petabytes of high resolution images are tragically gathering dust in data centers owned by Amazon (in the case of Maxar) and Google (in the case of Planet and Airbus).⁵

Meanwhile, if you listen to the executives of these companies speak publicly, they talk enthusiastically about the irreplaceable role that their data has to play in quantifying the effects of climate change, documenting the horrors of human rights violations, disrupting illicit trade networks, and mitigating a litany of other highfalutin problems facing humanity.

I agree with their assessment! Every week I meet more and more entrepreneurs, researchers, and philanthropists working tirelessly to convert raw satellite data into products that predict, preempt, and pacify human suffering and inequity.

My point is this: if you’ve generated archival data that is being kept in a state where it doesn’t produce significant shareholder value, and yet you know it has the potential to create immense societal value, do you have an ethical duty to release it to the world?

In my opinion, the obvious answer is YES, provided you can do it sustainably, which I believe you can.

The Economic Argument for Lettin’ It Rip

I’ve talked to a lot of smart people in this industry, including current and former executives at dozens of satellite imagery companies. Almost no one disagrees that “old” imagery should be easier to gain access to. In my opinion, it’s just a matter of degrees—maybe for one provider it’s ten years and older, and for another it’s only 90 days and older.

People disagree about the way the data should be licensed, the way access should be screened (due to security concerns), the leverage that cloud providers should have in whatever solution is offered, and other details. But all of those can be overcome with a little consistent effort. And yet, they haven’t been. What gives?

My theory as to why this data remains locked away and largely unused boils down to three reasons:

Reputational Risk | Doing something no one has ever done creates serious, potentially career-ending professional risk. The risk-reward ratio on a personal level for these executives makes advocating for this strategy fairly unappealing. Even if a CEO believes in this idea, they have to face a board who almost certainly won’t find it compelling at first glance. No one ever got fired by the board for not giving their archive away.

Credibility | Part of the narrative these executives have sold investors is that their unique proprietary advantage includes unique access to an archive no one else has. They may even assign a real dollar value to it as an intangible asset on their books. Giving the archive away would basically require admitting you aren’t going to be the all-things-to-all-people-AI/ML-overlords you may have once pitched investors on and outdated raw data is actually worth what people pay for it: practically nothing.

Motivation | Executives are motivated by the incentives designed by their boards. No one is getting a fat bonus for *checks notes* giving stuff away. For the publicly traded companies, especially, boards would seemingly rather see revenue increase a little every quarter than stomach two quarters of declining revenue in exchange for two subsequent years of rapid growth. Opening archival data is a 10-year bet on the creativity of entrepreneurs to build an entirely new economy of monitoring products. In other words, it’s a distraction from hitting month-end sales goals.

If you agree with me that we are undergoing a tectonic shift from the mapping paradigm of old to the monitoring business case of the future, then your attitude toward releasing old data is probably similar to mine.

I believe giving away archival data will result in several benefits that ultimately drive more demand for timely subscription and tasked data far in excess of the lost revenue from archival sales. Those benefits are:

Market expansion | Getting access to data requires dealing with a seemingly endless queue of sales people who are trained to look for what worked in the past, not what will work in the future. Open archives would allow new prospects to skip the inane sales back-and-forth and bring the cost of experimentation to ~zero, both in terms of time and money. It’s hard to quantify the true attrition rate of an average satellite imagery sales process - I would bet the vast majority of leads never even bother to subject themselves to the first sales call. Open archives de-risk purchases of fresh data by providing an accurate baseline to understand performance historically, which results in faster product iteration, more products getting launched, and more companies getting started. In a mapping-centric model, old data may jeopardize fresh data sales, since foundational data like roads, buildings, and lakes don’t change that much in the course of a few years. However, in a monitoring-centric model, giving old data away actually increases demand for fresh data, because if you’re monitoring something you want to know what’s happening now, not what happened a year ago.

Fused datasets | Magic happens when you combine datasets. A “fused” product or derived dataset based on multiple sources is often more accurate, more resilient, and more easily generalizable than something built on a single input. Opening the archive would allow for novel fused datasets that for certain use cases would be more valuable than the sum of their parts. Researchers and philanthropists, and even some for-profit companies, would gladly donate their work back into the open. Over a three year period, which one do you think would produce more value for your company: your current IRAD initiatives or the cumulative creativity of the remote sensing community?

Organic marketing | Whoever first invented the map attribution requirements was a genius. I feel like DigitalGlobe is still a more recognizable brand than Maxar because of the many years of repetitive exposure on nightly news graphics. Just because you give the data away doesn’t mean you can’t require proper attribution. “© 2022 Satellite Imagery Co.” is our industry’s version of “Sent from my iPhone.” Every clever viral product and news story built on top of open archival data will have a legal obligation to credit their sources.

If, like me, you believe opening old data will steadily increase demand for fresh data (where most of the profit comes from already), then you are left with one major hurdle: cost of service. It’s true that serving petabytes of data to customers all over the world incurs real costs. I suspect the cloud bill for some of these providers is already in the low-seven-figure-per-month range. So, how can you afford the spike in usage that would result from releasing your data?

There are two obvious options to me:

Strike deals with the cloud providers to host the data for free. You can still charge for downloads/egress (i.e. “requester pays”) and the cloud providers get to keep the upside of all the computation that occurs on their platforms.

Expand upon existing government initiatives to broaden access to archival data to the public. Either that’s revising the terms of defense contracts like whatever the next version of EnhancedView, or doubling down on civil gov’t deals like NICFI’s deal with Planet, NASA’s Commercial Smallsat Data Acquisition Program, or ESA’s past commercial data procurements.

Personally, I would pursue both simultaneously. Maybe option one yields results in the short term and option two makes it sustainable for the long haul.

Some have argued that giving cloud providers even more leverage over the future of remote sensing is a bad idea. I agree to an extent—Google likes to deprecate things that millions of people use daily for sport. Corporate charity is a fickle mistress.

However, since the majority of cloud provider’s profit allegedly comes from renting out compute, not storage, it’s probably a profitable deal for them even if they cover the hosting costs. And, because there are at least three major cloud providers who have already made huge commitments to remote sensing, competition is likely to incentivize good behavior.

I’m not too worried about giving cloud providers more “leverage.” It’s tough to imagine a scenario much worse than the status quo. As an industry, we have collectively chosen complacence in the face of terrific need.

It’s past time: open all of the satellite imagery archives.

¹ How can you tell someone got a liberal arts degree? We use “expound” instead of “expand upon” just to make our writing a little less accessible. Eat that, STEM nerds. Go read a really old book for once in your life, losers.

² If you don’t know what Landsat (NASA/USGS) and Sentinel-1/Sentinel-2 (ESA) are, they are scientific Earth observation missions involving large, exquisitely calibrated satellites that capture imagery of the entire globe on a regular cadence. Landsat is celebrating its 50th anniversary this year. In fact, there have been 9 different satellites bearing the Landsat name over those five decades—Landsat 9 was launched last year! The data they produce is open and hosted freely for anyone to access. Pretty wild.

³ According to NASA’s website, this led to a 60-fold increase in downloads. I suspect that’s hugely out of date. Look at the slope of the line between 2008 and 2012…then look at the slope between 2012 and today.

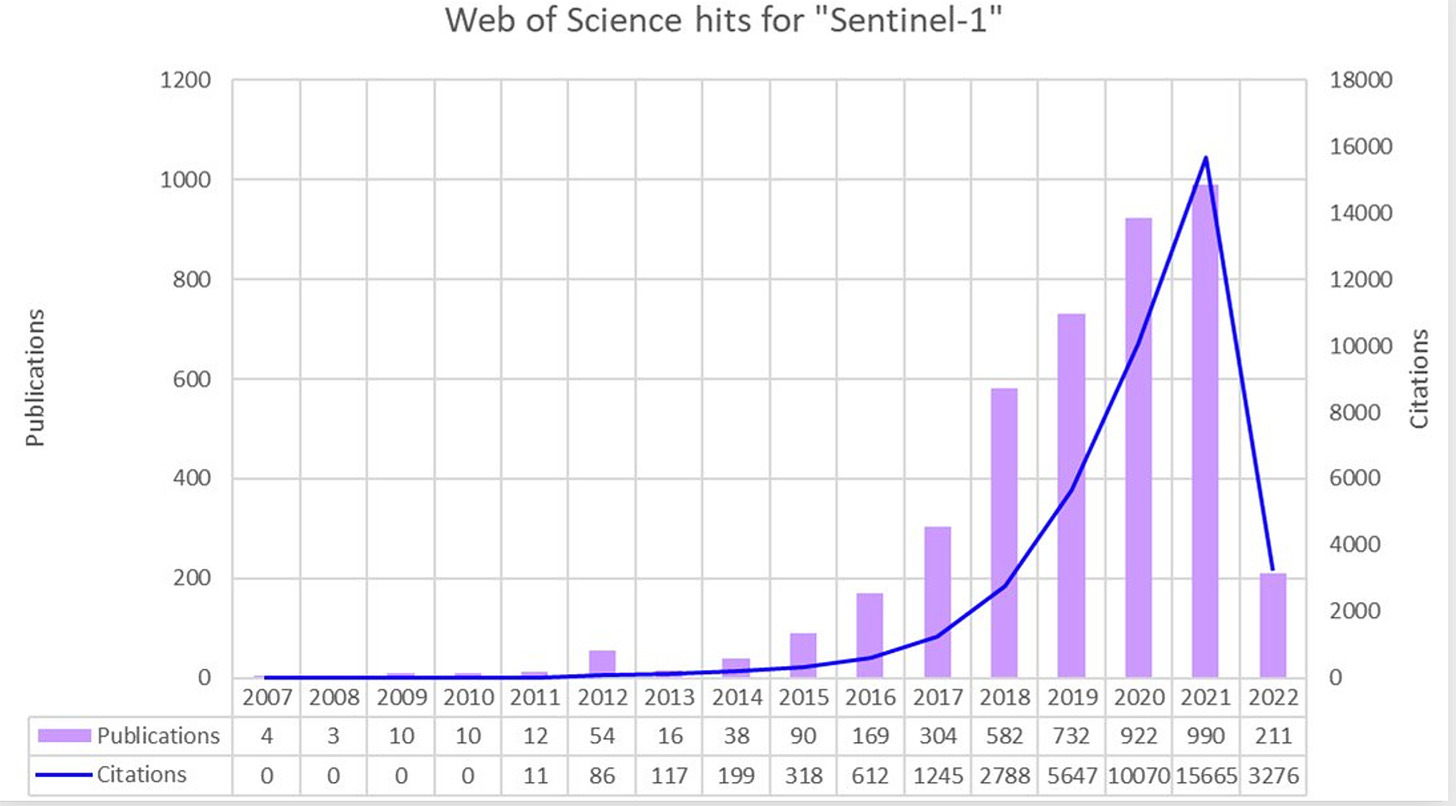

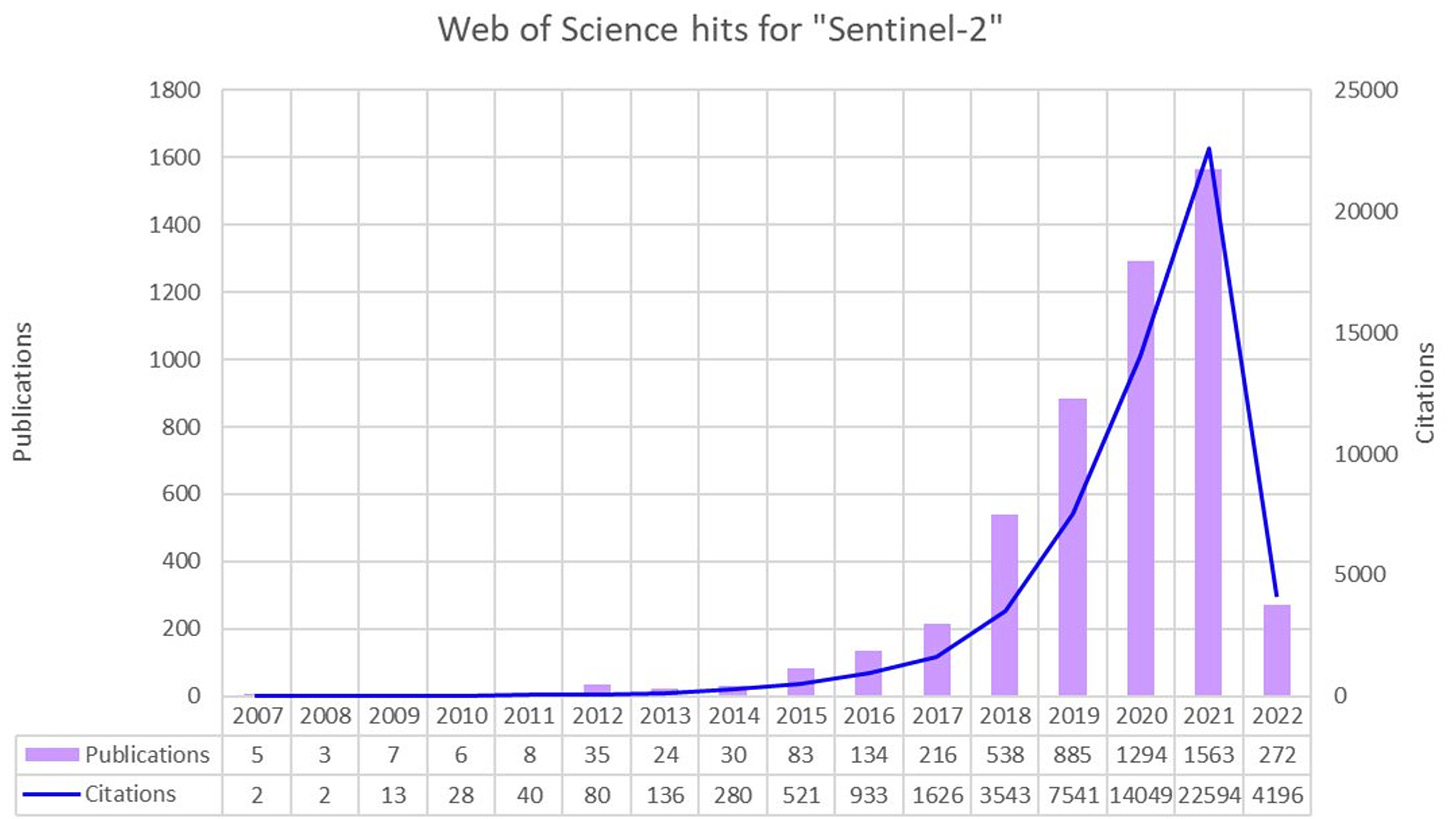

⁴ The same trend holds for Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 in case you’re thinking it’s a unique phenomenon (also courtesy of @sakkesarjakoski):

⁵ Maxar made a huge spectacle of migrating to AWS by literally driving a semi-truck of data into their maw, Planet sold off a large minority stake to Google in exchange for switching from AWS to GCP (and the SkySat née Terra Bella née Skybox assets), and Airbus is a featured case study on GCP’s blog.